Infrastructure as Code - An intro - Part 5 - Using Terraform

In this 5th entry in my IaC blog series, I want to talk about Terraform.

Terraform is a bit different from ARM and Bicep, which I covered in the previous post, as it isn’t Azure specific. Instead, it enables the user to deploy resources not only to Azure, but also to a lot of other clouds/systems. This makes it a more flexible alternative that is very useful if you need to deploy a mix of resources, or potentially not target Azure at all.

Note: At the time of writing, there were 1515 different providers available for use with Terraform. For an up-to-date list, have a look at https://registry.terraform.io/browse/providers

What is Terraform

Terraform is one of several products from HashiCorp. Most of them aim to help out with cloud native application development.

In Terraform, resources are defined using the HashiCorp Configuration Language (HCL). By using this “neutral” language and depend on separate providers for resource provisioning and management, it can be used to target a very wide set of systems and clouds. And by making the provider implementation open for anyone to implement, it allows all kinds of vendors to provide Terraform users with custom functionality to target their specific environment.

In the case of Azure, the Terraform provider is built on top of the Go SDK for Azure. This unfortunately means that there is often a delay between new features being released and Terraform offering support for them. The reason for this is that when a new feature is made available in the Azure API, the Go SDK must add support for it before someone can go ahead and add the feature to the Terraform provider. In a lot of cases, it isn’t a problem if you have to wait for a new feature for a few weeks, but I do find it worth mentioning if you are currently evaluating what IaC tool you should use.

Note: Missing features can often be handled using something called Terraform providers while you wait for native support.

Luckily though, the maintainers of the Terraform GitHub repos are generally very active, which means that most new features are quickly implemented. It also means that there is a lot of really good information and help available to you if you are having issues. And if you can’t find a solution, adding an issue in the repo tends to generate useful information within a short period of time.

State

The fact that Terraform isn’t bound to any particular system or cloud in the way that ARM/Bicep is, means that it cannot assume any specific functionality is available when it comes to the system it is working with. Because of this, Terraform maintains its own state in a JSON blob, which is used to “diff” the desired state and the current state when trying to figure out what changes are needed. With for example ARM/Bicep, this is not really required as it can “diff” against the existing environment in a fairly easy way.

Note: The state is definitely “readable” if you know what you are doing, but it should generally be left alone.

The state can be stored in a lot of different locations, using what is called backends. By configuring a backend you can select to store the state in a lot of different locations, such as the local system, Azure Blob Storage, Amazon S3 Buckets or in Terraform Cloud.

Note: Terraform Cloud is an online service that offers added benefits when it comes to storing and managing state.

However, it is important to understand that Terraform also refreshes the state from the target environment whenever it is trying to figure the changes that have been made. This means that it doesn’t solely rely on its own state when figuring out what actions need to be performed to get to the desired state. Instead, it uses a combination of its own state and the “real world” to figure out what changes need to be performed. This allows Terraform to revert changes that have been made to the target environment since it was last run, which in turn limits the amount of configuration drift that can happen. At least if Terraform is run at a reasonable frequency (not just once).

Terraform pre-requisites

The tools used for working with Terraform is somewhat similar to that being used for ARM/Bicep. It looks as follows

- Azure CLI

- The Terraform CLI

- A text editor of sorts. I recommend VS Code

- Optional: The Terraform extension for VS Code, which will give you some extra help when working with Terraform.

Note: I’m going to assume that you have the Azure CLI installed, as it has been used in the previous posts. If you haven’t, I suggest going back to the post about the Azure CLI and having a look at how to install it.

Terraform CLI

If you have a text editor and the Azure CLI installed, the only thing you need to install is the Terraform CLI. This is quite easily installed on most platforms. However, if you are on Windows, the recommended way is to use Chocolatey, which is an awesome package manager for Windows. And even if it might seem a little unfamiliar to use a package manager to install applications in a Windows environment, I definitely recommend trying it out. Especially since the other option is to download a ZIP-file with the CLI, and then manually update the PATH variable to include the location where you saved the executable.

Using Chocolatey, you just need start a Terminal with Administrator privileges and run

> choco install terraform

During the installation you will probably have to accept that it runs a PowerShell script, which is fine.

Once the install has completed, you can verify that everything has worked as it should by running

> terraform --version

Terraform v1.0.9

on windows_amd64

If it says that it can’t find the Terraform executable, try restarting your PowerShell prompt to reload the PATH variable.

Note: If it says that it is out of date, you just need to run choco upgrade terraform

That’s it! You are ready to go, unless you also want to use the Terraform extension for VS Code.

Terraform extension for VS Code

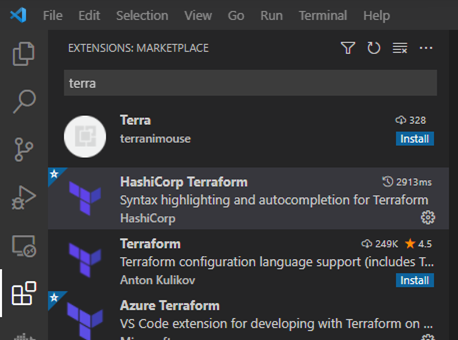

To install the Terraform extension in VS Code, you just need to go to the extensions tab and search for terraform. This should get you a bunch of results. The one you are looking for is the one called HashiCorp Terraform.

Once installed, it will be activated whenever you open a .tf file.

Setting up a Terraform project

“As usual” the target infrastructure looks like this

- A Resource Group to hold all of the resources

- An App Service Plan using the Free tier

- A Web App, inside the App Service Plan

- Application Insights (connected to the Web App)

- A Log Analytics Workspace to store the Application Insights telemetry

- A SQL Server Database

The Web App also needs to be connected to the SQL Server by a connection string in the Connect Strings part of the app configuration, and to the Application Insights resource by adding the required settings in the App Settings part.

All of this should be fairly familiar if you have read the previous posts. If you haven’t, then it will be news to you, but you will pick it up along the way anyway!

So…let’s go ahead and create our first Terraform file called main.tf.

Configuring Terraform

The first thing we need to do, is to configure the providers we want to use in our Terraform project. As we are only deploying to Azure in this post, we just need to configure the azurerm provider, which is done by adding a block of code that looks like this

terraform {

required_providers {

azurerm = {

source = "hashicorp/azurerm"

version = "=2.82.0"

}

}

}

This tells Terraform that we want to use a provider called azurerm, which can be located at the Terraform default registry using the path hashicorp/azurerm. It also defines that we want to use version 2.82.0.

Note: The configuration supports greater than syntax (´>´) for the version, however, I find that locking it to a specific version is less likely to cause problems. And it still allows us to easily upgrade it manually when the need for a newer version comes up.

Once the provider has been defined, we also need to add a default configuration for it by adding

provider "azurerm" {

features {}

}

This configuration allows us to configure global settings for the azurerm provider. However, in this case there is no global configuration required. The provider still requires a settings block with an empty features block inside it though.

Note: I’m not sure why this is needed, but if you leave it out you get an error saying Error: Insufficient features blocks

State storage

In this blob post, the state will be stored in the local folder, which works fine for simple demos and for trying things out. However, in a “real” scenario, you are likely going to store the state in a “central” location. So, I thought I would cover that very briefly.

To configure where the state is stored, you can use a “backend”. This is a concept that allows us to store the state in one of several available locations. For example, if you wanted to store the state in Azure Blob Storage, you could use a backend-configuration that looks like this

backend "azurerm" {

resource_group_name = "<RG NAME>"

storage_account_name = "<STORAGE ACCOUNT NAME>"

container_name = "<CONTAINER NAME>"

key = "<FILENAME>"

}

This is a bit outside of the scope for the current post, but if you want to have a look at how to work with backends, you can have a look at https://www.terraform.io/docs/language/settings/backends/index.html.

Creating a resource group

Now that we have configured Terraform, we can shift our focus to creating our first resource. In this case, that is the resource group that will hold all our resources.

To define resources in HCL, you use a syntax that looks like this

resource "<RESOURCE TYPE>" "<LOGICAL NAME>" {

<PROPERTY NAME> = <PROPERTY VALUE>

<PROPERTY BLOCK NAME> {

<PROPERTY NAME> = <PROPERTY VALUE>

}

}

For an Azure resource group, which is defined as the resource type azurerm_resource_group, it looks like this

resource "azurerm_resource_group" "rg" {

name = "TerraformDemo"

location = "westeurope"

}

In this case we are setting the name and location properties for the resource group, which are the only ones required. However, more complex resources will require more config.

The “logical” name, in this case rg, has nothing to do with the generated resource. It is simply a name used when referencing this resource in other parts of the template.

Note: You can find all the available resource types and their properties in the documentation for the AzureRM Terraform provider

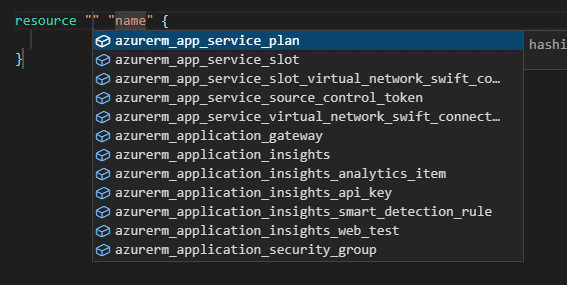

If you are using VS Code and the Terraform extension, it can help you with defining the resource. Just type res and then press Enter, and VS Code will give you suggestions that you can select from

And if you happen to close the helpful dropdown, you can re-open it by placing the caret between the quotes (") where you set the resource type and press Ctrl + Space.

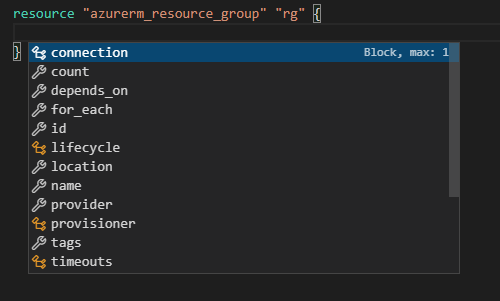

You can also use the Ctrl + Space command to get a list of available properties that can be set

And if you want the = signs to line up nicely, and you have the VS Code extension installed, you can just press Shift + Alt + f to format the file. And if you don’t have the extension, you can format all files in the current folder by running terraform fmt.

Note: In ARM/Bicep, it is not necessary to create a resource group if you deploy your template to a resource group, which is what I did in the previous posts. However, if you were to target another scope during the deployment, such as a subscription, then you would need to create a resource group in those languages as well.

Now that we have Terraform configured, and the first resource defined, we can try deploying it.

However, before we can deploy it, we need to initialize Terraform. This allows Terraform to look at the configuration and figure out what providers are being used, so that it can download the required binaries. It also locks in the current versions of the provider in a lock-file, which adds some extra safety if you use a non-specific version for a provider.

This is easily done by simply running

> terraform init

Note: When running terraform init, you are also able to provide custom backend configuration that you might not want to hard code in the Terraform file. This allows you to have different backend configuration for different releases for example.

Once the initialization has completed successfully, we can use Terraforms built in ability to verify that the code we have written is correct. This is a really fast way to verify that our code is correct, without having Terraform go through the whole state diff process. Just run

> terraform validate

Success! The configuration is valid.

Note: Running terraform validate is an optional step, but in a larger infrastructure set up, it can be a very fast way for you to quickly validate if you have missed something, used an incorrect reference, or maybe introduced a syntactical problem.

Ok, now that we know the code is valid, we can go ahead and see what actions Terraform believes it needs to perform to get to the desired state, by running

> terraform plan

Terraform used the selected providers to generate the following execution plan. Resource actions are indicated with the following symbols:

+ create

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# azurerm_resource_group.rg will be created

+ resource "azurerm_resource_group" "rg" {

+ id = (known after apply)

+ location = "westeurope"

+ name = "TerraformDemo"

}

Plan: 1 to add, 0 to change, 0 to destroy.

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Note: You didn't use the -out option to save this plan, so Terraform can't guarantee to take exactly these actions if you run "terraform apply" now.

As you can see from the last row before the line, it thinks that it needs to create a single resource, which is correct since we only have a single resource group defined so far

Note: When running terraform plan, it is possible to store the plan in a file for later deployment. This file is versioned, so if the plan isn’t valid at the time you want to run it, it will not allow you to use it.

Since Terraform was correct, we might as well go ahead and deploy it. However, make sure that you have selected the correct Azure subscription in the Azure CLI before you carry on. This is quite easily done by running az account show. The reason for this is that Terraform will use the same credentials as the Azure CLI by default.

If you have confirmed that the correct subscription is selected, you can go ahead and deploy the infrastructure by running

> terraform apply

Terraform used the selected providers to generate the following execution plan. Resource actions are indicated with the following symbols:

...

Do you want to perform these actions?

Terraform will perform the actions described above.

Only 'yes' will be accepted to approve.

Enter a value:

When running terraform apply without supplying a plan, it will actually perform a plan and then ask you to approve it, before actually deploying the resources. And since the plan looks good in this case, we can confirm by typing yes and pressing enter.

Note: In a non-interactive scenario, like a deployment pipeline, you can skip the manual approval step by adding an --auto-approve parameter

Once the deployment has completed, you will have a new file in your directory called terraform.tfstate. This file contains the state of the currently deployed infrastructure in JSON format. And even if it is human readable, I suggest not playing around with it too much, as any issue that you introduce will make it impossible to run Terraform.

Adding the SQL Database

Now that the resource group has been created, we can carry on and focus on the SQL Server and database. And since the database requires a server, let’s start with the SQL Server resource.

In Terraform, with the azurerm provider, the resource type used for a SQL Server resource is azurerm_mssql_server. This means that the resource definition will look like this

resource "azurerm_mssql_server" "sql" {

name = "mydemosqlserver123"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

administrator_login = "server_admin"

administrator_login_password = "P@ssw0rd1!"

version = "12.0"

}

This resource needs a few more properties than the resource group. Among them the name of the resource group (resource_group_name) and a location (location). As these values are the same as the ones used for the actual resource group, we can use that resource definition to set the properties. In Terraform you refer to a resource definition using the syntax <RESOURCE TYPE>.<LOGICAL NAME>.<PROPERTY NAME>. So, for the resource group’s location property, that turns into ` azurerm_resource_group.rg.location`.

I am also setting the server’s version and admin credentials, which are both required. However, I definitely want to say that I do NOT recommend hard coding the administrator credentials in the Terraform at all. We will come back to this and fix it, but for now, let’s just have these values hard coded.

Besides the hard coded credentials, this resource has another problem. The name. The name of a SQL Server instance has to be globally unique as it gets a DNS entry. And by using a hard coded name like mydemosqlserver123 we are very likely to get a naming collision. Either because someone else has already registered, or because we will have already registered it if we try to set up multiple environments. Because of this, it is wise to have some form of random part in the name. Not to mention that it is generally a good idea to have a naming standard in place that allows you to easily find a specific resource.

To sort out the random part, we can use a random_string resource, which is defined like this

resource "random_string" "suffix" {

length = 6

special = false

upper = false

}

This will create a resource called suffix that contains a random 6 character string, including only lower case letters and number.

As for the naming standard, we can implement a very simple one by using something like <PROJECT NAME>-<RESOURCE TYPE>-<RANDOM STRING> for the names of our resources. However, for that, we need a “project name”. Basically, a string representing the name of the project, that we can use when naming our resources. Like a variable. However, in Terraform it isn’t called a variable, it is called a “local”. And “locals” are defined in a locals block like this

locals {

project_name = "MyDemo"

}

With those things in place, we can use string interpolation to update the SQL Server name to implement our naming standard

resource "azurerm_mssql_server" "sql" {

name = " ${local.project_name}-sql-${random_string.suffix.result}"

...

}

There are three things to note here.

First of all, the string interpolation syntax. By using the ${ ... } syntax inside of a string, you can add dynamic parts to the string.

Secondly, you declare “locals” using locals (plural), but you reference “locals” using local.<NAME> (singular).

And finally, the way to get the random string from the random_string resource is by using the result property.

In the end, it should look something like this

locals {

project_name = "MyDemo"

}

resource "random_string" "suffix" {

length = 6

special = false

upper = false

}

resource "azurerm_mssql_server" "sql" {

name = " ${local.project_name}-sql-${random_string.suffix.result}"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

administrator_login = "server_admin"

administrator_login_password = "P@ssw0rd1!"

version = "12.0"

}

It might be worth mentioning that the order in which you declare things doesn’t matter in Terraform. Instead, Terraform will always load and parse all .tf files before evaluating the resource hierarchy. However, I personally do prefer having the Terraform config at the top, then “locals” and other resources that are used shared, and finally the individual resources. At least if it is a really small infrastructure. Otherwise, I prefer separating the resources into “logical” groups in separate files. But that’s just me…

However, if you were to run terraform validate right now, you would get an error like this

Error: Could not load plugin

Plugin reinitialization required. Please run “terraform init”.

Plugins are external binaries that Terraform uses to access and manipulate

resources. The configuration provided requires plugins which can’t be located,

don’t satisfy the version constraints, or are otherwise incompatible.

Terraform automatically discovers provider requirements from yourconfiguration, including providers used in child modules. To see therequirements and constraints, run “terraform providers”.

failed to instantiate provider “registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/random” to obtain schema: unknown provider “registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/random”

The reason for this is that the random_string resource is in an implicitly referenced provider called hashicorp/random. And since that wasn’t used when we ran terraform init, it didn’t know that it needed to download that provider as well.

To solve this, we can simply re-initialize Terraform and get the new provider downloaded by running

> terraform init

Success! The configuration is valid.

Now that the server has been defined, we can define the database.

resource "azurerm_mssql_database" "db" {

name = "MyDemoDb"

server_id = azurerm_mssql_server.sql.id

collation = "SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS"

sku_name = "Basic"

}

Once again, it is just a few properties that need to be defined. However, there are a lot more if you need other settings than the defaults.

For the database, we do not need to have “cattle-based naming”. This is going to be referenced by our application, so it should have a “proper” name. Also, it doesn’t need to be unique outside of the actual server, so simple, “proper” names are fine.

The last part of the database puzzle is the fact that the server firewall needs to be opened. And for the sake of simplicity in this case, I suggest opening it for all Azure services. This is done by adding a firewall rule that opens an IP span from 0.0.0.0 to 0.0.0.0. And with the azurerm Terraform provider, that means creating an azurerm_mssql_firewall_rule resource

resource "azurerm_mssql_firewall_rule" "allow_all_azure_ips" {

name = "AllowAllWindowsAzureIps"

server_id = azurerm_mssql_server.sql.id

start_ip_address = "0.0.0.0"

end_ip_address = "0.0.0.0"

}

That’s it! Let’s see what changes Terraform thinks it needs to perform to get to the desired state

> terraform plan

Terraform used the selected providers to generate the following execution plan. Resource actions are indicated with the following symbols:

+ create

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# azurerm_mssql_database.db will be created

+ resource "azurerm_mssql_database" "db" {

+ auto_pause_delay_in_minutes = (known after apply)

+ collation = "SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS"

+ create_mode = "Default"

...

}

# azurerm_mssql_firewall_rule.allow_all_azure_ips will be created

+ resource "azurerm_mssql_firewall_rule" "allow_all_azure_ips" {

+ end_ip_address = "0.0.0.0"

+ id = (known after apply)

+ name = "AllowAllWindowsAzureIps"

+ server_id = (known after apply)

+ start_ip_address = "0.0.0.0"

}

# azurerm_mssql_server.sql will be created

+ resource "azurerm_mssql_server" "sql" {

+ administrator_login = "server_admin"

+ administrator_login_password = (sensitive value)

+ connection_policy = "Default"

+ name = (known after apply)

...

}

Plan: 3 to add, 0 to change, 0 to destroy.

──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Note: You didn't use the -out option to save this plan, so Terraform can't guarantee to take exactly these actions if you run "terraform apply" now.

Ok, it thinks it needs to add 3 things, which looks correct.

An interesting thing here is that it says that the SQL Server name is (known after apply). This is because we are using string interpolation to create the name. And since the interpolation uses the random_string resource, it won’t actually know the value until that resource has been created, which doesn’t happen until terraform apply. Luckily, Terraform knows how to handle this, so we can just go ahead and interpolate as much as we want.

Also, if you run this on your own machine, you will notice that I cut out fairly sizable chunks of information about the db and server. The reason for this is that it outputs every single property with their default values, which becomes a bit much for this blog post. However, it can be an extremely useful thing to look at, as it not only tells you exactly what properties are available, and the default values, but it often reminds us of properties we forgot to set. At least I find that it reminds me of things quite often.

Since the plan seems to be ok, let’s go ahead and run

> terraform apply

And approve the changes by entering yes and pressing enter.

Now that the database is in place, we can go ahead and focus on the web app!

Creating the Azure Web App

However, before we can create the app, we need to create the app service plan. Luckily, this is a pretty simple resource type called azurerm_app_service_plan that needs little configuration

resource "azurerm_app_service_plan" "plan" {

name = "${local.project_name}-plan-${random_string.suffix.result}"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

sku {

tier = "Standard"

size = "S1"

}

}

Nothing really new in here! It’s just a matter of figuring out what properties need to be set, which is pretty well defined in the Terraform documentation for the azurerm provider.

Next up is the actual web app, which is also fairly simple do define using the ` azurerm_app_service` resource type

resource "azurerm_app_service" "app" {

name = "${local.project_name}-web-${random_string.suffix.result}"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

app_service_plan_id = azurerm_app_service_plan.plan.id

}

As you can see, it just needs a name, resource group and location, like most resources, and the ID of the app service plan resource we just created.

However, to make it run ASP.NET Core applications, which is what we want, we need to set the dotnet_framework_version property of the web app’s site_config block to "v5.0". Like this

resource "azurerm_app_service" "app" {

...

site_config {

dotnet_framework_version = "v5.0"

}

}

We also need to add a connection string to the database in the web app’s connection strings collection, which is available through the connection_string block. In this case, it should be called connectionstring, be of type SQLAzure and contain the connection string to the database. This means that it will look like this

connection_string {

name = "connectionstring"

type = "SQLAzure"

value = "Data Source=tcp:${azurerm_mssql_server.sql.fully_qualified_domain_name},1433;Initial Catalog=${azurerm_mssql_database.db.name};User Id=${azurerm_mssql_server.sql.administrator_login};Password='${azurerm_mssql_server.sql.administrator_login_password}';"

}

Since the connection string isn’t available through Terraform, but all the individual pieces are, we can use string concatenation to generate the required connection string.

But…this looks like a single thing, not an array or list. What if we want to specify more than one connection string? Well, you just add another connection_string block, and you are good to go.

There is one more thing that might be worth mentioning. As the connection string uses the SQL Server resource during the string concatenation, Terraform will automatically figure out that the server needs to be created before it can create the web app. However, in some cases the relationship isn’t as obvious. And in those cases, you can explicitly set up these dependencies using the depends_on list. So, if there wasn’t a connection string being set up like this, but the app was still dependent on the SQL Server, we could have added a depends_on entry like this

depends_on = [

azurerm_mssql_server.sql

]

But as I said, Terraform is smart enough to figure it out automatically in this case.

Now that the all the resources needed for the application is fully defined, we can have a look at defining the “supporting” resources. That is the Application Insights and the Log Analytics Workspace it will use to store its data.

Setting up Application Insights using a Log Analytics Workspace

As I mentioned before, the order in which you set up resources in doesn’t matter in Terraform. However, it is still easier to go through and define them based on how they depend on each other. And in this case, the Application Insights resource depends on the Log Analytics Workspace, so let’s start with the workspace.

resource "azurerm_log_analytics_workspace" "ws" {

name = "${local.project_name}-ws--${random_string.suffix.result}"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

}

There isn’t a whole lot to talk about when it comes to this resource. Especially since we depend on the defaults for all the settings except the mandatory ones.

And the Application Insights resource isn’t much more intriguing to be honest

resource "azurerm_application_insights" "ai" {

name = "${local.project_name}-ai--${random_string.suffix.result}"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

workspace_id = azurerm_log_analytics_workspace.ws.id

application_type = "web"

}

Sure, it requires the ID of the Log Analytics Workspace resource, and an “application type”. But that’s about as thrilling as it gets. However, we aren’t quite done yet. We also need to set a few “app settings” in the web app to connect it to the Application Insights.

The settings that need to be set are

- APPINSIGHTS_INSTRUMENTATIONKEY – The unique key generated by the Application Insights resource

- APPLICATIONINSIGHTS_CONNECTION_STRING – The connection string to the Application Insights resource

- ApplicationInsightsAgent_EXTENSION_VERSION – Set to

~3for Linux and~2for Windows - XDT_MicrosoftApplicationInsights_Mode – Set to

recommendedfor…well…recommended data gathering

To set the “app settings” for the web app, we use the app_settings property. This property is defined as an object, and each property on the defined object is turned into a setting in the web app. So, to set the required settings, we can add

resource "azurerm_app_service" "app" {

...

app_settings = {

APPINSIGHTS_INSTRUMENTATIONKEY = azurerm_application_insights.ai.instrumentation_key

APPLICATIONINSIGHTS_CONNECTION_STRING = azurerm_application_insights.ai.connection_string

ApplicationInsightsAgent_EXTENSION_VERSION = "~3"

XDT_MicrosoftApplicationInsights_Mode = "recommended"

}

}

That’s it! The infrastructure is now defined as needed. However…there are quite a few hard coded values that would make sense to have as input parameters instead, as this would allow us to re-use the same template to create multiple environments with slightly different configuration. For example, it might be interesting to have a smaller app service plan for dev/test, than for production.

Defining input variables

In Terraform, input parameters actually called input variables, and they are defined using variable blocks. These are blocks defining not only the available inputs, but also their type and potential default values. And if you want to, you can also give them a description to describe what they are used for.

In the current infrastructure, I see at least 6 values that could/should be turned into input parameters. They are

- The project name

- The size of the SQL database

- The admin credentials for the SQL Server

- The SKU information for the App Service Plan

However, the current main.tf file is getting somewhat big. And since Terraform parses all .tf files in the current directory when run, I suggest adding the variable declarations in a new Terraform file called inputs.tf instead.

Inside this new file, we can add variables using the following syntax

variable "<VARIABLE NAME>" {

type = <TYPE>

default = "<DEFAULT VALUE>"

description = "<DESCRIPTION>"

sensitive = <true | false>

}

However, only the type is required. The other properties are optional. However, if you do not add a default value, the parameter is considered required, and you will be prompted for it unless you provide it when running Terraform.

Note: You can also add value validation, but that is outside the scope of this post. But if you want to know more about the more advanced possibilities when it comes to input variables, you can have a look at https://www.terraform.io/docs/language/values/variables.html

Now that we know how to define input variables, we can go ahead and add the 6 variables we need for this demo

variable "project_name" {

type = string

description = "The name of the application"

}

variable "sql_size" {

type = string

description = "The SQL Server database size"

default = "Basic"

}

variable "sql_user" {

type = string

description = "The username to use for the SQL Server Admin"

default = "server_admin"

}

variable "sql_pwd" {

type = string

sensitive = true

description = "The password to use for the SQL Server Admin"

}

variable "app_svc_plan_sku_tier" {

type = string

description = "The service plan tier"

default = "Free"

}

variable "app_svc_plan_sku_size" {

type = string

description = "The service plan size"

default = "F1"

}

These are fairly easy to grasp, I think. The only things that might be a bit interesting to note are the lack of default values for project_name and sql_pwd, and the sensitive property added to the sql_pwd.

The lack of default values is due to the fact that these 2 values should never be “defaulted”. The project_name should always be defined, as re-using the same project name, in this case, would cause naming conflict. And the password should obviously be unique, and never ever be checked into source control.

The sql_pwd has also been marked as sensitive. This makes sure that the value is not output in the plan or apply output. However, it is still added to the state, so anyone with access to the state can still read it.

Ok…now that we have the input variables defined, we can update the template to make use of them. The only thing we have to do, is to locate all the hard coded values that should be updated and replace them with the variable values. And the syntax for that is var.<VARIABLE NAME>.

The first thing that needs updating is the local project_name. However, as some resources are case sensitive, I suggest that we make sure to turn the provided value into lower case while we are at it.

locals {

project_name = lower(var.project_name)

}

Converting the value to lower is done using the built-in function lower(). Terraform has a bunch of these function that you can use. You can find a complete list at https://www.terraform.io/docs/language/functions/index.html.

The next step is to replace the rest of the hard coded values. Like this

resource "azurerm_mssql_server" "sql" {

...

administrator_login = var.sql_user

administrator_login_password = var.sql_pwd

...

}

resource "azurerm_mssql_database" "db" {

...

sku_name = var.sql_size

}

resource "azurerm_app_service_plan" "plan" {

...

sku {

tier = var.app_svc_plan_sku_tier

size = var.app_svc_plan_sku_size

}

}

That’s it! No more hard coded values!

But how do we set these values? Well, there are two different ways. The first is to create a .tfvars file that contains the values. This can then be passed to Terraform during plan and apply by using the -var-file=<PATH TO FILE> parameter

To try this out, we can go ahead and create a new file called terraform.tfvars and add the following line to it

project_name = "MyDemo"

The other way is to provide the values using the -var "<VARIABLE NAME>=<VALUE>" parameter when executing terraform plan or terraform apply, which is what I would recommend doing with the SQL Server password for example.

If we decide that we are OK with the default values and want to provide the project_name input using the .tfvars file, and the SQL password using a -var parameter, it will look like this

> terraform apply -var "sql_pwd=P@ssw0rd!" -var-file ./terraform.tfvars

However, if you approve the suggested changes, you will end up with an error that looks something like this

Error: Error creating App Service “mydemo-web-nh3xo6” (Resource Group “TerraformDemo”): web.AppsClient#CreateOrUpdate: Failure sending request: StatusCode=0 – Original Error: autorest/azure: Service returned an error. Status=<nil> <nil>

with azurerm_app_service.app,

on main.tf line 77, in resource “azurerm_app_service” “app”:

77: resource “azurerm_app_service” “app” {

The reason for this is that when we set the default values for the App Service Plan SKU, we used the “Free” tier. This tier unfortunately is limited to running a 32-bit worker process and does not support “Always On”. Unfortunately, this conflicts with the Terraform defaults for these settings.

To solve this, we need to make sure that the worker process and “Always On” settings are set to the correct value if the SKU tier is set to “Free”.

These settings are defined under the site_config block on the web app. However, as the values need to change depending on the configured input values, we will need to use a couple of conditional statements.

In Terraform, you can do conditional value setting by using the syntax <BOOLEAN EXPRESSION> ? <TRUE VALUE> : <FALSE VALUE>. So, to set the correct configuration for the web app, we can use the following code

resource "azurerm_app_service" "app" {

...

site_config {

...

always_on = lower(var.app_svc_plan_sku_tier) == "free" ? false : true

use_32_bit_worker_process = lower(var.app_svc_plan_sku_tier) == "free" ? true : false

}

}

The use of the lower() function is just to make sure that we are doing a case insensitive comparison.

Once that is in place, you should be able to run another terraform apply with the correct -var parameter like this

> terraform apply -var "sql_pwd=P@ssw0rd!"

In this case I actually left out the -var-file parameter. The reason for this is that if you name the .tfvars file terraform.tfvars, it is actually added automatically even if you don’t provide the -var-file parameter. The same is true for any file named .auto.tfvars.

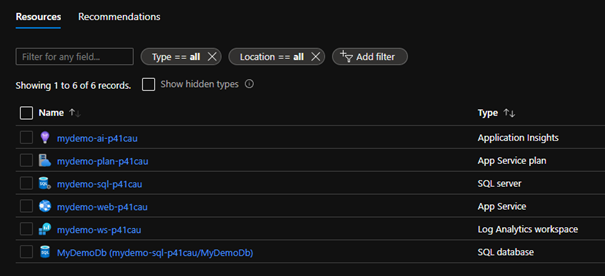

If you go ahead and approve the suggested changes, you should end up with an environment that looks like this (except for the random suffix of course)

Sweet! The only thing left now, to make it “just like” the previous demos, is to add an “output” for the website address.

Outputs

Often when running IaC, you need to get values from the IaC data so that it can be used in later steps in the release pipeline, or maybe as a config value for some other application. The way that you do this in Terraform is by using what is called “outputs”.

Outputs are basically just pieces state information that you want to have available. In this example infrastructure, it is likely that we would want to get hold of the address to the web app, as this includes the random suffix. The way we do this, is by defining and “output”.

Outputs are defined using the following syntax

output <NAME> {

value = <VALUE>

}

In this case, we want to output the default_site_hostname of the web app. However, that property is only the host name, and does not include the “https://” part. To fix that, we can simply use string interpolation. Like this

output "website_address" {

value = "https://${azurerm_app_service.app.default_site_hostname}/"

}

Now that the output has been defined, we need to re-run terraform apply to get it added to the state

> terraform apply -var "sql_pwd=P@ssw0rd!"

Once Terraform has applied the changes (added the output to the state), we can go ahead and read the output value by running

> terraform output website_address

"https://mydemo-web-p41cau.azurewebsites.net/"

An annoying thing here is that the value is surrounded by double quotes, which can cause some major problems when using it in things like scripts. Because of this, Terraform has a parameter called -raw that allows us to get the output value without the quotes.

> terraform output -raw website_address

https://mydemo-web-p41cau.azurewebsites.net/

That’s it! Now you know how to set up Terraform, define resources, and deploy them to Azure! That’s all this post was to cover. However, it might be a good idea to clean up the resources now that we are done with them. For this, Terraform has the terraform destroy command.

There is one little caveat with the destroy command though. It requires all input variables to be set. However, the actual values don’t matter during destroy, as the state already contains all the resources that need to be removed. So, if you want to destroy the current infrastructure, you have to remember to include the sql_pwd input

> terraform destroy -var "sql_pwd=''"

...

Destroy complete! Resources: 9 destroyed.

Your Azure subscription should now be back to the state it was before you started!

Conclusion

Terraform is definitely a different thing than ARM and Bicep, even if the syntax is actually quite similar to the one used by Bicep. Under the hood, it works in a completely different way, using the Azure REST API instead of talking directly to the Azure Resource Manager. The downside to this is that any new features being added to Azure will first have to be released in the REST API, then in the Go SDK, and finally in the Terraform Azure provider. A chain of events that might take a while.

Having that said, this is only really an issue if you are using bleeding edge features. If not, pretty much all other features are supported. The flip side to this is obviously that by using a provider-based system, Terraform is able to target a lot of different clouds and systems. Which in turn allows you to use your IaC not only for your Azure resources, but potentially for a bunch of different systems and clouds. Something that ARM/Bicep will never be able to do.

The fact that it doesn’t talk to the Azure Resource Manager and manage state using the “real” world is a potential problem. However, the fact that Terraform uses a mix of “local” state and “real world” makes this a non-issue in my world. It even seems to make Terraform perform a bit faster than ARM/Bicep.

So, if you need to go outside the realm of Azure, where ARM/Bicep is not going to cut it, I think Terraform is an awesome option. On the other hand, if you are strictly Azure focused, and have no other clouds/systems you want to integrate with, I think Bicep might be an equally good option.

But keep in mind, we still have one more contender to look at, and that’s Pulumi. An IaC tool that also utilizes the benefit of the provider-based architecture, but also adds the ability to use a real programming language when creating your desired state. So, the jury is still out!

The 6th part in this series about IaC talks about Pulumi! You can find it here: Infrastructure as Code - An intro - Part 6 - Using Pulumi

Feel free to reach out and give feedback or ask questions! I’m available on Twitter @ZeroKoll.